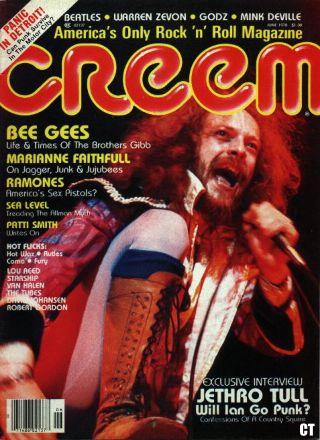

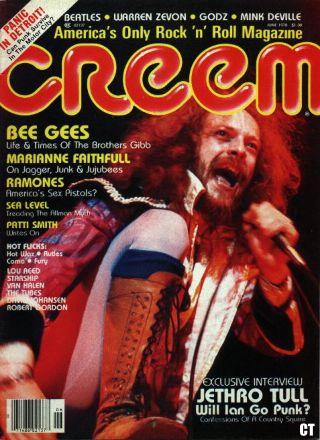

Jethro Tull

Creem Magazine [June, 1978]

Ian Anderson rules OK. For an hour I've been waiting in the foyer, talking

to his manager, his wife, watching his employees bustle about. It's Maison

Rouge, Anderson's property and one of the nicer recording studios in London--small,

relaxed, without the desperate hip of most of the specialist rock places.

A money maker, though, and when Anderson arrives it's as the boss. He's

been lunching with TV people, planning a Tull feature in an arts show.

Ian Anderson rules OK. For an hour I've been waiting in the foyer, talking

to his manager, his wife, watching his employees bustle about. It's Maison

Rouge, Anderson's property and one of the nicer recording studios in London--small,

relaxed, without the desperate hip of most of the specialist rock places.

A money maker, though, and when Anderson arrives it's as the boss. He's

been lunching with TV people, planning a Tull feature in an arts show.

Anderson is wearing

tight brown cords, a shiny camouflage jacket and one of those dumb, Jethro

Tull-type pork pie hats. He's better looking than I expected and much more

charming. On the rock writing circuit he's got a bad reputation, as arrogant

and tedious, and it has been a long while since Jethro Tull got reviews

to match their sales, but now, Anderson's qualities seem different-professional,

articulate, interesting. His arrogance is there alright but it rests not

on self pride but on his determination to take charge of whatever he's

involved in, to do a good job. This is an interview job and so he takes

it over. He doesn't suffer fools gladly, especially when he's working,

and my CREEM tag set him briefly bristling, remembering his last CREEM

occasion, when Lester Bangs took him on and shouted him to a tense tie.

This time he's not going to lose control. He eyes my clumsy cassette and

warns that "I talk quickly because I don't want to have to lie. If I talk

fast enough I haven't got time to think about if it's lying or not so it's

probably going to be the truth."

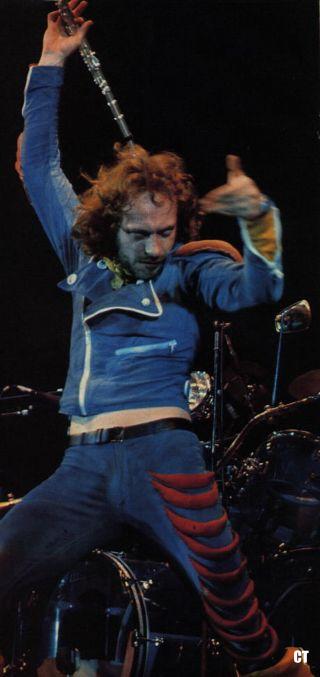

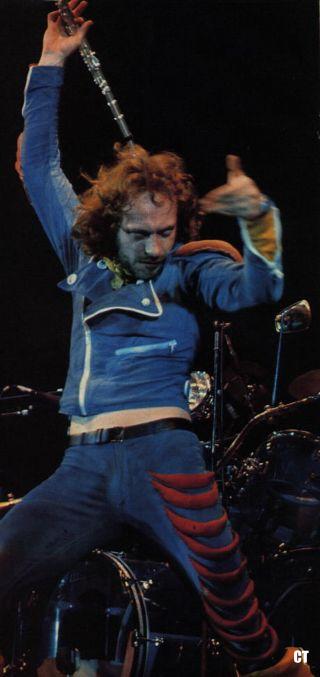

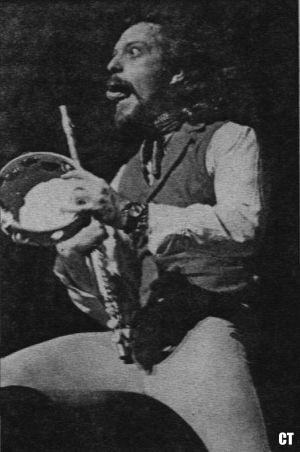

I'm uneasy enough as

it is, without this threat. The only reason I decided to do this interview

was out of hostility. I've never liked Jethro Tull much, found the music

both fey and turgid and never listened enough to hear the lyrics. Anderson

himself, one-legged like a stork, is a fetishized flute player, his fans'

estimations of his skill way beyond anything I've heard him achieve...Earlier

I'd heard his wife say that Ian didn't allow their young son to go to Tull

gigs because he wouldn't understand what Daddy was doing. I don't go to

Tull gigs either, and for the same reason. I've never understood Tull's

appeal. There are lots of other bands that I don't like but millions do

but I can hear why. Tull, on the other hand, make no sense to me whatsoever

and that's really the only question I came here to ask: why on earth should

anyone fancy you?

But Anderson's too clever, too impressive for me to put it like that and

the question comes out different, like it's my fault not his and I'm asking

him to help me become a Tull fan too. And he's not that helpful, doesn't

understand much himself. Begin with the audience:

But Anderson's too clever, too impressive for me to put it like that and

the question comes out different, like it's my fault not his and I'm asking

him to help me become a Tull fan too. And he's not that helpful, doesn't

understand much himself. Begin with the audience:

"I've really no idea

who they are and I've really no idea what they like about us. I posed this

question on the last tour in America, particularly at the end of last year's

tour, because the audience was so overwhelmingly young again. There was

this incredible element of fifteen and sixteen-year-old kids there, who

would have been seven or eight when we started and I don't know why they're

there because why aren't they supporting the trendy up-and-comings? Why

aren't they supporting their own heroes instead of latching on to the heroes

of the Generation before them? I don't know the answer. I find it distinctively

worrying. I'm very gratified that they're there and people say I should

be really pleased because this is your audience for the next five or ten

years--you've actually broken that age barrier, they're yours. But I still

find it worrying. I find it worrying because why weren't the Sex Pistols

doing it already? Why aren't all the other groups who've had a go and haven't

made it? In America particularly, and on the world stage, there still seems

to be this handful of groups and most of them are British. It's your problem

as a sociologist and it's my problem only in that I feel some responsibility

for the fact that they're there, perhaps getting beaten up or mugged on

their way home. That's the only way it worries me, because I can't really

probe into the whys and wherefores of who they are and the reasons they

like Jethro Tull. I don't know.

So. Does Anderson still

believe in his old 60's notion of rock progress, of his audience growing

up with him?

"I think that notion died on most of us five years ago because it became

firmly apparent that at the age of 25 or thereabouts most people get married,

most people have a kid and take on the responsibilities of a wife and child,

a mortgage, their per capita half a swimming pool and three-quarters a

Chevy or Ford Cortina. They have all these things and music becomes a luxury

and competition becomes greater for that audience. They arguably have more

money to spend and I'm not suggesting that Elton John or Fleetwood Mac

or Peter Frampton --all these people--deliberately set out for a middle

of the road audience, it may be accidental that their choice of music appeals

to those people. I hope so for their sake. But in my case it would be a

deliberate attempt, if I made one, to reach out to that vast middle of

the road audience.

"I think that notion died on most of us five years ago because it became

firmly apparent that at the age of 25 or thereabouts most people get married,

most people have a kid and take on the responsibilities of a wife and child,

a mortgage, their per capita half a swimming pool and three-quarters a

Chevy or Ford Cortina. They have all these things and music becomes a luxury

and competition becomes greater for that audience. They arguably have more

money to spend and I'm not suggesting that Elton John or Fleetwood Mac

or Peter Frampton --all these people--deliberately set out for a middle

of the road audience, it may be accidental that their choice of music appeals

to those people. I hope so for their sake. But in my case it would be a

deliberate attempt, if I made one, to reach out to that vast middle of

the road audience.

But why should over-25s

be middle of the road?

"There's something

rather sobering about having domestic responsibilities that inevitably

rub off on your taste. It's horrible to have to equate a sober taste with

someone like Fleetwood Mac, but Fleetwood Mac obey all the rules, they

really do--musically, harmonically and stylistically they obey the rule

book, I mean to the letter and they do it pretty well. And that, if you

like, is a sobering quality which is readily embraced by people who don't

have the fervent sort of listening approach of adolescents really identifying

with something. They want music to relax to more than music to get fired

up to.

"And that's why it's

a shame that the punk rock thing is so laden with the fact that it's very

derivative musically of things that you and I are familiar with--the rock,

the riffs, the beat. We've all heard and experienced it probably twice

already. Punk rock is just another time for the same old tried and tested

elementary rock riff, same old electric guitar, same old drum kit set up

the same old way. And it's so class-ridden, 'the music of the working class'.

The great thing when I came in was that it was classless. It was great

back then. People did cross the borders of style and class. But the punk

thing is a working class thing and so you only get someone hyphen something

following punk out of a terrible mixed-up rebellious thing."

Does that mean that Jethro Tull are going to be the classless musicians

for the teenage generation forever? Is Ian Anderson still going to be a

teen idol at age 50? 60? 70?

Does that mean that Jethro Tull are going to be the classless musicians

for the teenage generation forever? Is Ian Anderson still going to be a

teen idol at age 50? 60? 70?

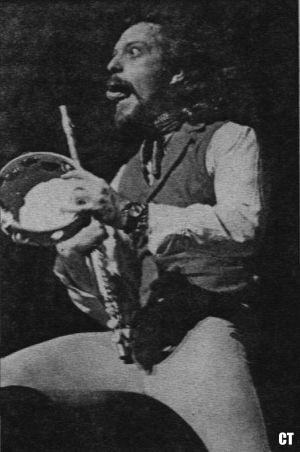

"No, I can't see it.

I find it a little bit disturbing to walk out on stage and see two 14-year-old

girls screaming just like I seem to remember on newsreel seeing them do

that to the Beatles. And I'm thinking it's 1977 (it was when I was last

on stage) and here's a couple of little girls, much too young to copulate

with, and there they are actually screaming and doing a number equivalent

to Beatle mania. I think this can't be. I'm 30 now and this just isn't

really decent. But it's still marginally acceptable at the age of 30. At

the age of 40 it's going to be quite indecent. No one's got there yet,

but Mick Jagger's well on the way. Nobody's got too old to rock 'n' roll

but there is a difference between being 40 and being 30 or even 35, 36,

37.

By this time I'm finding

it hard to get a word in but what I want to ask is what Jethro Tull actually

sing about, what it is they think they're doing when they're doing it and

how this aging is affecting it. I don't get to ask this very clearly but

it does emerge that Anderson is a great Ian Dury fan, partly because Dury

doesn't pretend to be young.

"I thought to myself

last night: I wonder what he would think of my music. I actually like him

and I don't like many people and I'm sure he wouldn't say 'Oh, I like your

music too' because he probably doesn't. And he'd probably say 'You're not

singing about life out there on the streets and things as they really are.'

My answer would have to be 'Well, I did once upon a time, seven or eight

years ago. I did then but if I'd carried on singing about that for seven

or eight years I would now be living a very conspicuous lie because I do

not choose and no way am I going to carry on living in a bed sitter.

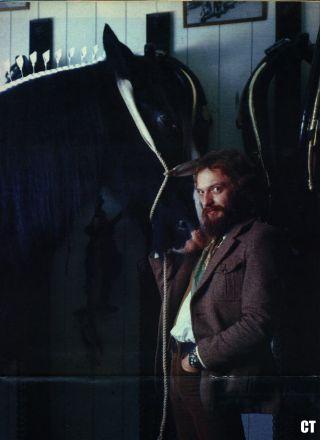

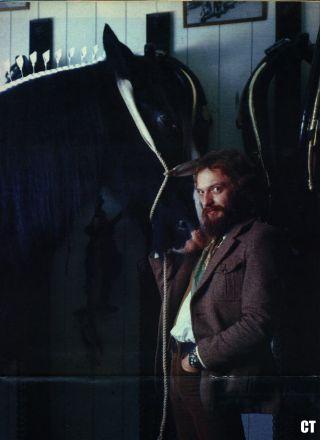

"I did do it to the

point when it was absurd. I had a number one record and I still lived in

a three pound a week bedsit and it was obviously not right anymore. I wasn't

kidding anyone and it would be silly for me to do that now. I like my dogs

and cats and horses and my house and the things that I have, that I've

worked really hard for. These are the things I enjoy. They're not things

I own--I don't believe in ownership of these things--they're things that

I've somehow paid in hard cash for the right to enjoy. And I do enjoy them.

They mean an awful lot to me.

"I'd like to think

that someone like Ian Dury, say he was inordinately successful for five

years, would have the same problems as I have had in terms of what shall

I do with the money? You can blow it on parties, dope, flash cars, private

cinemas but perhaps because I'm Scottish, too canny, I refuse to throw

it away. I would rather have something tangible at my disposal and also

something I can feel a little bit responsible for. That's one thing money

buys: the right to acquire responsibility for things or people or animals

or whatever.

"I try to write songs that aren't too different from the way I live and

so my songs have necessarily had to change, as I've grown away from having

a working group sort of life. As the logic of success prevailed we made

a commitment to going first class in the world and then it suddenly dawned

that it's not on to sing as if we're sitting down there. We're not anymore.

We're sitting up here. And we can't really sing about sitting up here because

that's irrelevant to most people and sounds a bit cocky, so it became a

little more abstract. Lyrically things became more abstract and started

taking on weird and weighty connotations, which were amusing for a bit,

amused me, but after a while you want to get back to the direct meaningful

songs that are about something and actually deal in fairly accessible English.

You're forced to think what is there to write about, what moves me, and

that's what I write about now, whatever it is that's left.'

"I try to write songs that aren't too different from the way I live and

so my songs have necessarily had to change, as I've grown away from having

a working group sort of life. As the logic of success prevailed we made

a commitment to going first class in the world and then it suddenly dawned

that it's not on to sing as if we're sitting down there. We're not anymore.

We're sitting up here. And we can't really sing about sitting up here because

that's irrelevant to most people and sounds a bit cocky, so it became a

little more abstract. Lyrically things became more abstract and started

taking on weird and weighty connotations, which were amusing for a bit,

amused me, but after a while you want to get back to the direct meaningful

songs that are about something and actually deal in fairly accessible English.

You're forced to think what is there to write about, what moves me, and

that's what I write about now, whatever it is that's left.'

"Stylistically, I've

always said that we can't be a heavy riff group because Led Zeppelin are

the best in the world. We can't be a blues-influenced r&b rock and

roll group because the Stones are the best in the world. We can't be a

slightly sort of airy-fairy mystical sci-fi synthesizing abstract freak-out

group because Pink Floyd are the best-in the world. And so what's left?

And that's what we've always done. We've filled the gap.

We've done what's left.

That may partly explain our popularity and we've done it for the most part

without the aid of gargantuan feats of PR and manipulating the daily press

with scandal stories. And we still are one of the most popular groups in

the world. There is no explanation. At the same time as being one of these

top groups, we are somehow not. We are somehow different."

It's true. Jethro Tull

are different in their lack of flash, their lack of hype, their lack of

parasites, their lack of personality--I can't even remember who else is

in the band. Tull musicians don't encourage groupies and they aren't groupies

themselves--no hanging out with the international rock jet set.

Anderson, with his confidence and responsibilities and aloof efficiency,

is a country squire of the most traditional sort. His conversation was

studded with anti-Americanism (he likes Ian Dury for his cockney vowels,

for example) and Songs From The Wood, the last Tull album, sounded pretty

much like straight old country folk to me. Anderson defies any purist folkie

leanings but he did describe the new album, Heavy Horses, as Songs From

The Wood Part 2 plus a bit more Jethro Tull, and his concern did seem to

be that it not be heard as twee.

Anderson, with his confidence and responsibilities and aloof efficiency,

is a country squire of the most traditional sort. His conversation was

studded with anti-Americanism (he likes Ian Dury for his cockney vowels,

for example) and Songs From The Wood, the last Tull album, sounded pretty

much like straight old country folk to me. Anderson defies any purist folkie

leanings but he did describe the new album, Heavy Horses, as Songs From

The Wood Part 2 plus a bit more Jethro Tull, and his concern did seem to

be that it not be heard as twee.

But it is a British

country record, celebrating shire horses and Anderson's dog and cats on

a track called "And The Mouse Police Never Sleep. Not twee, because not

romantic and not hippie is Anderson's hope. It's about town and country,

the former's dependence on and exploitation of the latter. I didn't hear

it and probably never will. But when I left I touched my forelock. Anderson

was very gracious and I started musing that if Tull's success is based,

as Anderson at some point said, on "a lucky coincidence", then there must

be millions more potential country gentry wandering about Britain's pubs

and clubs, guitars clutched in sticky hands, waiting for their lucky break.

They're mostly disguised as punks at present.

Written by: Simon Frith

Ian Anderson rules OK. For an hour I've been waiting in the foyer, talking

to his manager, his wife, watching his employees bustle about. It's Maison

Rouge, Anderson's property and one of the nicer recording studios in London--small,

relaxed, without the desperate hip of most of the specialist rock places.

A money maker, though, and when Anderson arrives it's as the boss. He's

been lunching with TV people, planning a Tull feature in an arts show.

Ian Anderson rules OK. For an hour I've been waiting in the foyer, talking

to his manager, his wife, watching his employees bustle about. It's Maison

Rouge, Anderson's property and one of the nicer recording studios in London--small,

relaxed, without the desperate hip of most of the specialist rock places.

A money maker, though, and when Anderson arrives it's as the boss. He's

been lunching with TV people, planning a Tull feature in an arts show.

But Anderson's too clever, too impressive for me to put it like that and

the question comes out different, like it's my fault not his and I'm asking

him to help me become a Tull fan too. And he's not that helpful, doesn't

understand much himself. Begin with the audience:

But Anderson's too clever, too impressive for me to put it like that and

the question comes out different, like it's my fault not his and I'm asking

him to help me become a Tull fan too. And he's not that helpful, doesn't

understand much himself. Begin with the audience:

"I think that notion died on most of us five years ago because it became

firmly apparent that at the age of 25 or thereabouts most people get married,

most people have a kid and take on the responsibilities of a wife and child,

a mortgage, their per capita half a swimming pool and three-quarters a

Chevy or Ford Cortina. They have all these things and music becomes a luxury

and competition becomes greater for that audience. They arguably have more

money to spend and I'm not suggesting that Elton John or Fleetwood Mac

or Peter Frampton --all these people--deliberately set out for a middle

of the road audience, it may be accidental that their choice of music appeals

to those people. I hope so for their sake. But in my case it would be a

deliberate attempt, if I made one, to reach out to that vast middle of

the road audience.

"I think that notion died on most of us five years ago because it became

firmly apparent that at the age of 25 or thereabouts most people get married,

most people have a kid and take on the responsibilities of a wife and child,

a mortgage, their per capita half a swimming pool and three-quarters a

Chevy or Ford Cortina. They have all these things and music becomes a luxury

and competition becomes greater for that audience. They arguably have more

money to spend and I'm not suggesting that Elton John or Fleetwood Mac

or Peter Frampton --all these people--deliberately set out for a middle

of the road audience, it may be accidental that their choice of music appeals

to those people. I hope so for their sake. But in my case it would be a

deliberate attempt, if I made one, to reach out to that vast middle of

the road audience.

Does that mean that Jethro Tull are going to be the classless musicians

for the teenage generation forever? Is Ian Anderson still going to be a

teen idol at age 50? 60? 70?

Does that mean that Jethro Tull are going to be the classless musicians

for the teenage generation forever? Is Ian Anderson still going to be a

teen idol at age 50? 60? 70?

"I try to write songs that aren't too different from the way I live and

so my songs have necessarily had to change, as I've grown away from having

a working group sort of life. As the logic of success prevailed we made

a commitment to going first class in the world and then it suddenly dawned

that it's not on to sing as if we're sitting down there. We're not anymore.

We're sitting up here. And we can't really sing about sitting up here because

that's irrelevant to most people and sounds a bit cocky, so it became a

little more abstract. Lyrically things became more abstract and started

taking on weird and weighty connotations, which were amusing for a bit,

amused me, but after a while you want to get back to the direct meaningful

songs that are about something and actually deal in fairly accessible English.

You're forced to think what is there to write about, what moves me, and

that's what I write about now, whatever it is that's left.'

"I try to write songs that aren't too different from the way I live and

so my songs have necessarily had to change, as I've grown away from having

a working group sort of life. As the logic of success prevailed we made

a commitment to going first class in the world and then it suddenly dawned

that it's not on to sing as if we're sitting down there. We're not anymore.

We're sitting up here. And we can't really sing about sitting up here because

that's irrelevant to most people and sounds a bit cocky, so it became a

little more abstract. Lyrically things became more abstract and started

taking on weird and weighty connotations, which were amusing for a bit,

amused me, but after a while you want to get back to the direct meaningful

songs that are about something and actually deal in fairly accessible English.

You're forced to think what is there to write about, what moves me, and

that's what I write about now, whatever it is that's left.'

Anderson, with his confidence and responsibilities and aloof efficiency,

is a country squire of the most traditional sort. His conversation was

studded with anti-Americanism (he likes Ian Dury for his cockney vowels,

for example) and Songs From The Wood, the last Tull album, sounded pretty

much like straight old country folk to me. Anderson defies any purist folkie

leanings but he did describe the new album, Heavy Horses, as Songs From

The Wood Part 2 plus a bit more Jethro Tull, and his concern did seem to

be that it not be heard as twee.

Anderson, with his confidence and responsibilities and aloof efficiency,

is a country squire of the most traditional sort. His conversation was

studded with anti-Americanism (he likes Ian Dury for his cockney vowels,

for example) and Songs From The Wood, the last Tull album, sounded pretty

much like straight old country folk to me. Anderson defies any purist folkie

leanings but he did describe the new album, Heavy Horses, as Songs From

The Wood Part 2 plus a bit more Jethro Tull, and his concern did seem to

be that it not be heard as twee.