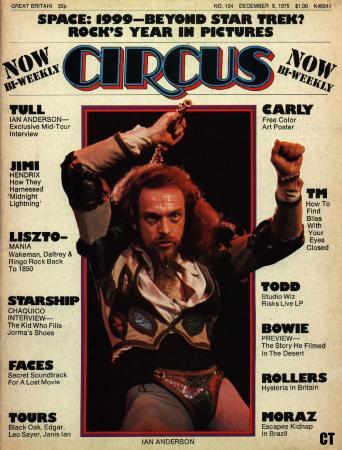

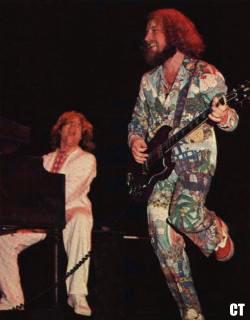

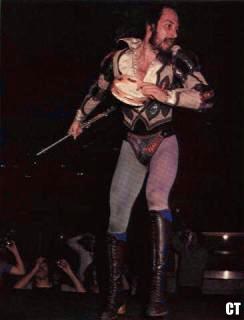

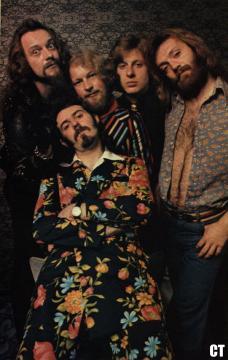

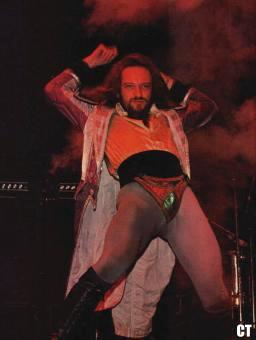

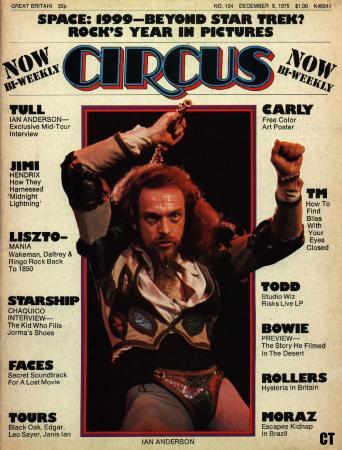

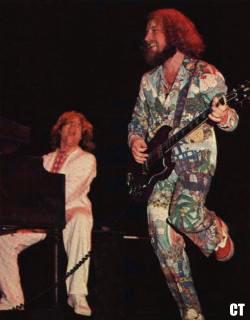

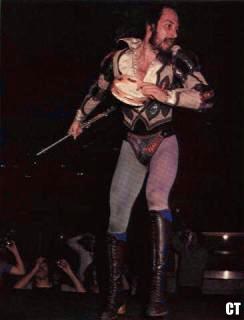

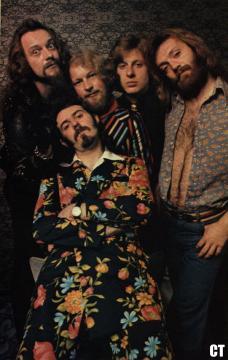

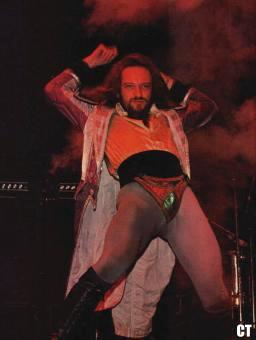

Jethro Tull

Circus Magazine [December 9, 1975]

Ian Anderson is not fond of the press; in fact, he dislikes that

body intensely. Interviews have misquoted him, misrepresented him and manhandled

him. In a line from "Baker Street Muse" (a song from the new Minstrel In

The Gallery album) he sings, "I have no time for Time or Rolling Stone,"

and one must wonder why he consented to this conversation at all.

Ian Anderson is not fond of the press; in fact, he dislikes that

body intensely. Interviews have misquoted him, misrepresented him and manhandled

him. In a line from "Baker Street Muse" (a song from the new Minstrel In

The Gallery album) he sings, "I have no time for Time or Rolling Stone,"

and one must wonder why he consented to this conversation at all.

The talk took place over

three days and in two states, North Carolina and Confusion. At various

times the tape was running in hotel rooms, backstage dressing areas, airport

snack bars, and airplanes; interruptions were frequent as Ian is always

in constant demand by his road manager and band members. But never once

did he fail to keep an appointed session without prior notice.

Anderson is a difficult

man to know and hopefully the following will help you figure him out. A

single question elicits a precise, often lengthy response, which covers

not only the area in question but any boundary points. He smokes and drinks

coffee continuously and will entertain dialogue as long as his cigarette

is kept lit and his cup full.

This, then, is the main

body of those conversations. All the words are Ian's, all the thoughts

his own; what were once private sentiments, are here now printed. Now they

belong to you. [SR]

Circus: For starters,

once you've finished an album such as Minstrel In The Gallery, does it

remain with you? Does the music become a part of you?

Anderson: After all

the actual recording is finished you have to mix it, play the tapes to

cut it, listen to tape lacquers and cut it again, and make changes and

cut it again, and finally make test pressings--it drags it out. So it doesn't

get finished really for quite awhile after the music's finished; when it's

actually ready to go it's nothing to do with me anymore. It's already with

them, I mean they can do what they like with it. They pay $6 for the privilege

...

Unless I continue to play

the songs onstage if they're those kind of songs that continue with me

in a personal way by playing them as part of the show every night. Then

I feel closer, perhaps, to the music. Not the album per se, but the music

itself.

Circus:

How do you feel when somebody attacks this music you're somewhat attached

to?

Circus:

How do you feel when somebody attacks this music you're somewhat attached

to?

Anderson: If somebody

says, 'I think your music is shitty,' that's like saying, 'I think your

wife's a whore.' And I get very angry when people say that behind my back

or via the unassailable media of the press. Because I'm not in a position

to defend it and I won't be brought out or taunted by public criticism

into answering it back in the same medium. Because I can never win, I'm

not a journalist, and I'm not in a position to see that my words remain

undistorted or in the true context when they finally appear in print. I

don't have the same control of that sort of expression in its final form

as I do on record or performing onstage. So I'm naturally wary of being

drawn out.

And I have a fairly low

opinion of the press because I think it plays way below the average level

of intelligence of the audience who reads it. I think it sets out purely

to survive with the basest instincts of survival. And that about answers

everything I have to say anticipating your questions about my attitude

towards the press and why I don't do many interviews.

Circus: Actually,

that was one question I wasn't going to ask because I knew that you didn't

like doing interviews.

Anderson: No, well

I don't, but I thought I'd answer it anyway by asking it myself. To save

you the embarrassment of why you hadn't managed to ask me.

Circus: Well,

I tried to come in here with a knowledge of your music and yourself, whatever

that means to you.

Anderson: Well, it

obviously means you derive some amusement or entertainment out of listening

to what it is I do. And that's all I can ask of anyone and that's great--but

it's a coincidence as far as I'm concerned. It doesn't mean that I'm good

or you are particularly together or understanding. It is just coincidence;

if you happen to like it and I happen to like it, it just means we're more

often than not at the same football game together. We're on the same side

of the stands, watching the same team from the same end wearing the same

colors. But it doesn't mean that either of us is right or wrong. Maybe

Led Zeppelin have actually got it right... I heard one of their songs one

the way here in the car and the words sounded like a three-word thing and

it had 'Love' in it. Anyway, the chorus kept coming in and it was like,

'Gimme love' or something, some banal exultation.

Circus: You

hold Zeppelin in some disdain ?

Anderson: No, I think

they're one of the best rock and roll groups there are; I think musically

they're very good and I think what they represent in terms of the rock

group idiom is very accurate. They're a very accurate portrayal... they

epitomize, if you like, the English hard rock thing better than the Stones

probably and better than the Who. I mean, they're arrogant and they all

play with some sort of conviction, but as to whether what they do is worth

anything in the long run then history will, as usual, retrospectively decide.

I don't know, I don't understand

it; maybe there's more to it than meets the eye. I think about that a lot

actually. I think there's maybe more to a lot of things I don't understand.

Maybe it's because they're so simple, they're so good. But I write really

simple songs too, I've written some really simple ones, really crystal

clear. But they seem to have a lot more in them than other people's very

simple songs. There's a few of them on the new album, there's always bits

of them on all albums. "Wond'ring Aloud" was a simple song, a very simple

sentiment and quite an accurate one as well.

Circus: But

even your simple songs involve clever time changes and word patterns.

Anderson: I don't

think it's clever, I don't think I ever kept anything I did when I set

out to be clever. I mean, I have written and arranged things just to be

clever but they sounded like Yes played backwards or the Mahavishnu Orchestra

slowed down. But I didn't keep them, they weren't for anything, they weren't

saying anything It was just academic, an exercise.

Circus:

You talked about the music you didn't like--is there any particular piece

you've written which stands as your favorite?

Circus:

You talked about the music you didn't like--is there any particular piece

you've written which stands as your favorite?

Anderson: In different

ways, yes. The best album overall, if you're dividing music up into units

approximated in a certain year and being part of the package, I mean the

best album as a whole I think is definitely Passion Play. But there are

other albums which have some pretty stuff which doesn't hold up any longer,

they have some little things which are accidentally very fine things. I

mean Aqualung had some good bits on and War Child and Minstrel In The Gallery

have some good bits on, but I think overall they don't stand up as a whole

thing the way Passion Play did. It was a sort of total emotional thing

for me from the beginning to the end ...it's very gripping and I'm very

honestly moved by it. I hear it about once a year; I've heard it a couple

times since it came out, and I've actually been incredibly moved by it

both times. Having forgotten the arrangement and what the music was doing,

I found it a very energized sort of music. I'm well pleased with that aspect

of it.

Circus: What

about some of the earlier Tull albums like Benefit?

Anderson: It's not

one of my favorite albums. It's the one that means least to me because

I can't remember anything about recording it. I can't remember anything

that was going on then, I can't remember what I was trying to write. I

genuinely didn't know what I was doing then at all. I just really can't

remember why I wrote the songs on that album. I can remember what some

of the songs are but I can't remember why. I must have thought it was important

at the time or I would have just gone straight on to the next one. That's

funny actually, but I really can't remember it at all, it's the one that's

a blank to me, I can't figure it out.

It was a product, you see,

of being on tour in America very heavily in '69, the beginning of '70.

That was a very destructive year for me, that first year of touring in

the States. It was very hard work because we had to go economy everywhere

on the planes and we were losing an awful lot of money.

Circus: How

many American tours did it take for Tull to start making money?

Anderson: We did

a thirteen week tour the first time where we lost a lot of money and the

second time we did a lot of dates supporting Led Zeppelin as the opening

act. We just about broke even on that tour and on the third tour, the last

tour in '69, we came in and did some shows sort of on our own really--small

theatres and things. We made a little bit back on that. And then in '70

we actually began to co-host shows with groups like Mountain and that sort

of thing, middling name groups where it was a toss-up as to who went on

first. '71, '72, and '73 we made money and paid back everything we owed

in England put a lot of money into the group-the PA, trucks, stages, light

rigs, and sound equipment.

Circus:

How can you make money on a tour like you're now on, playing small halls

in relatively small cities?

Circus:

How can you make money on a tour like you're now on, playing small halls

in relatively small cities?

Anderson: I don't

know if we can afford to do these gigs again. See, I've always worked on

the philosophy that we can go out and gross about two or three million

dollars on a seven-week tour if we play football stadiums and outdoor shows

and concentrate on all the major markets and none of the smaller ones.

We can do a very big gross, the same as Zeppelin and the Stones do. But

I never thought that I'd be justified then in writing MUSICIAN on my passport

where it says occupation, which is what I am, that's what I do. And if

we were to go out and play football stadiums and not play the smaller halls,

even though there might be 5, 6, 7,000 people who want to come and see

the group, we would be much better off. We could lie low most of the year,

lay off most of the crew, but then it would have to say on my passport

ENTREPRENEUR, not MUSICIAN. If you're a musician and going to play to people

at all, you've got an obligation to go wherever people are, and not just

do it wherever the money is right.

Circus: So you'll

end up making about $2.50 an hour then?

Anderson: About $250

an hour wouldn't be far off.

Circus: The

band probably made about $250 when it first started; what were those early

days like?

Anderson: Well, Tull

first got together so everybody in the band could earn a living. I was

at school and art school after that and I decided I wanted something more

immediate in terms of doing something. So I decided to be a musician. I

wasn't that keen on music really, I wasn't wild about it. It just seemed

more immediate than painting. I started playing music when I was about

16, 17, and got into the origins of what was popular in the contemporary

sense--the Beatles, the Stones, and all that. I got into the origins of

their music, where they'd lifted it from-Howlin' Wolf, Muddy Waters, Sonny

Boy Williamson, and all the rest.

I began to write music and

developed a certain basic ability with instruments and a crude understanding

of the musical vocabulary that one has to have in order to write or appreciate

or simply understand music. No one ever taught me to read or write music

or play an instrument, it was just the painful process of working it out

yourself. How to make pleasing noises.

So at the time when I was

of an age to be professional--and being professional meant earning a living-it

was necessary to play some kind of music that was acceptable commercially

in the club circuit in England which was sort of a basic blues. We did

all the Elmore James and Sonny Boy Williamson material re-vamped into a

contemporary white English way.

There were two types of

groups at that time; there were the blues groups and the progressive groups

as they were called. Pink Floyd and the Nice and we were sort of stuck

somewhere between the two really.

Circus:

When did you first start playing flute?

Circus:

When did you first start playing flute?

Anderson: I used

to play the guitar before I went to London and wasn't a very good guitar

player, I couldn't afford strings ... I think I only had five anyway on

a very old Fender Stratocaster. It was a white Stratocaster; I thought

it was white until it actually chipped and I realized there were 17 coats

of paint underneath it, all the different colors it had been. I sold the

guitar, well, actually I exchanged the guitar since I couldn't get any

money for it. I exchanged it for more practical things to take on my journey

to the south. With knotted handkerchief on end of stick I set off to be

a success in England. I traded in the guitar for something easy to carry

and it was a flute and a microphone. I had it when I went to London and

I played it when we formed the group.

I nearly got thrown out

of the group because nobody had ever heard of a flute in a blues band.

Ten Years After told their manager that it was not right to have a flute

in a blues group so they tried to get me thrown out; they wanted me to

play rhythm piano at the back of the stage and let Mick Abrahams do all

the singing. That was something I fought strongly against ... I wasn't

a very good singer but he wasn't either. We used to do about half of it

each. I mean that was almost like getting thrown out of the group. What

it actually was was a polite invitation to leave. But I wasn't completely

aware of that, I sort of hung in there and at a certain point in time some

of the songs I had written and some of the things I was doing obviously

became the feature of the group.

Circus: Who

actually started Jethro Tull ?

Anderson: Well, it

was a peculiar situation. All the people in the group now apart from Martin

[Barre, guitarist] were in a seven-piece group as amateurs and we decided

to go to London end do it professionally. But after a week in London the

others changed their minds and we had no money, no food, and no prospect

of any work. I think we had about four or five dates set, about one a week

for the next four weeks or something, but I mean clearly we couldn't live,

clearly we weren't going to get given a bunch of dates to be able to pay

for things. So everybody packed up and went back after a few days because

we couldn't even eat. We found some potatoes in a cellar of this rented

basement that we managed to get and roasted them over a coke fire...nearly

all died from carbon monoxide poisoning. So they all went back. We actually

had gone down to work with this guitarist, Mick Abrahams, because he was

going to join the group. And when the others went back Mick and I decided

that if I could manage to stay down there and exist on nothing as it were,

he knew a drummer and I knew a bass player, and we could put together a

little group that would be cheaper to run. So I took a job vacuum cleaning

a cinema for which I got paid $15 a week which was just enough to pay the

rent. And managed to exist for a couple of months while we got some work.

That's how it began, it wasn't really that anybody started the group, it

was just the remnants of other groups.

Circus: Why

has Jethro Tull never recorded a live album?

Anderson: Well we

did about a month ago in Paris. We recorded and filmed about an hour and

ten minutes of selected pieces that in fact we'll do some more work on

as soon as we finish this tour. We did it really just to have some material

in the proverbial can for an eventual video disc or whatever video media

are introduced as a public concern. I mean that's obviously some few years

off, but anyway we'll probably bring out an album late in '76. In late

November a Best Of album comes out, then in the summer of '76 a group album

comes out. And at the end of '76 there'll be another Best Of album, which

will either be an all live album or else one side will be live and the

rest of it will be selected studio tracks that haven't been released on

a compilation album before.

The first Best Of album

will all be material which has been released before except one track called

'Rainbow Blues." I don't really like Best Of albums but I must admit among

my rarely played record collection, which isn't particularly large, are

a number of those types of albums by other artists. I don't have any of

the Cream's albums but I have two of their Best Of albums because they

have the songs that I like best by the Cream on them. Or Jimi Hendrix or

whatever. You see, there aren't that many people who have all of Jethro

Tull's records; they might have one or two and ...

Circus: I don't

think that's true.

Anderson: Oh, you'd

be surprised. I'm not just talking about the States, I'm talking about

all the countries in the world where a lot of our albums have never even

been released. There are a lot of people over here who only know Jethro

Tull since Thick As A Brick. I remember in '74 I received an enormous amount

of mail, more than ever before, from America. And almost all of it was

from kids of high school age and a lot of them said, 'I've never heard

Jethro Tull before, I'm 15, and I've just bought Passion Play, and I really

like it and can you tell me how many other albums you've released.' And

I thought that was incredible. I mean, they didn't know anything about

Aqualung or Benefit or Stand Up that was way before their time. One must

necessarily believe that those letters are in some way representative of

something and for all the letters sent there's a lot not sent from similarly

disposed people. And I must, therefore, believe there are a lot of kids

who don't have those earlier records.

Circus:

Do you see music going in any direction?

Circus:

Do you see music going in any direction?

Anderson: What I

think at the moment is ...this is a crude generality and the argument is,

full of holes but it stands up in some way. Twelve, fifteen years ago we

were in the midst of a very pop oriented scene. Everything was very stylized,

and what sold was of a very limited musical nature. It was simple music,

very technique written; the techniques weren't so advanced production-wise

and recording-wise as they are now, but nonetheless they were well-tried,

well-executed techniques. To wit: all those early rock and roll records

with their echo effect, multi-tracked tambourines-the Phil Spector sound.

Very naive music and naive lyrics but very catchy because everyone could

relate to them.

Most of these rock groups

had their origins in the pop music a few years before...Ritchie Blackmore,

Jimmy Page, all those, guys played on pop sessions. Keith Emerson used

to play in a soul group, Jon Anderson from Yes used to play in a group

called the Warriors that used to play Top 20 hits. We used to play blues

and soul music hits of the day when we were semi-pro.

We went through that formula

kind of music and then we went through this period where some of the artists

started writing their own music, with "Mack The Knife" and so on actually

getting into the charts. Progressive rock music as opposed to the pop music

of before--songs that they'd written themselves, arranged themselves, totally

free from the stranglehold of the record company molding their career and

their repertoire.

And the audience was the

audience who had grown up listening to early rock and roll, who then went

on to listen to these groups as they became more sophisticated. And now

they're the rather more adult audience of today. But now a lot of that

audience are getting almost as old as the members of the groups so they're

not so likely to go to rock concerts, not so likely to rush out and buy

the new record the day it's released. Their place is being taken by the

new generation of younger kids, the new 13, 14, 15 year olds who have created

a demand for simpler, more immediate music. Which is again a slicker, more

production-ridden gimmicky version of the early rock and roll. That is

what is hugely popular now in England. This simple sort of bubblegum rock

is what has taken over--and those records sell more than Led Zeppelin sell,

more than the Rolling Stones sell, more than Pink Floyd sells, more than

Jethro Tull sells. England had T. Rex, now it has the Bay City Rollers,

Mud, Slade, all kinds of names.

When this contemporary young

audience in two or three years is bored with this elemental rock and roll,

then when it gets of a drinking age it will find itself in the clubs and

pubs and will breed a new cycle of club underground groups. Out of that

will come the new Pink Floyds and Jethro Tulls.

Written by: Steve Rosen

Ian Anderson is not fond of the press; in fact, he dislikes that

body intensely. Interviews have misquoted him, misrepresented him and manhandled

him. In a line from "Baker Street Muse" (a song from the new Minstrel In

The Gallery album) he sings, "I have no time for Time or Rolling Stone,"

and one must wonder why he consented to this conversation at all.

Ian Anderson is not fond of the press; in fact, he dislikes that

body intensely. Interviews have misquoted him, misrepresented him and manhandled

him. In a line from "Baker Street Muse" (a song from the new Minstrel In

The Gallery album) he sings, "I have no time for Time or Rolling Stone,"

and one must wonder why he consented to this conversation at all.

Circus:

How do you feel when somebody attacks this music you're somewhat attached

to?

Circus:

How do you feel when somebody attacks this music you're somewhat attached

to?

Circus:

You talked about the music you didn't like--is there any particular piece

you've written which stands as your favorite?

Circus:

You talked about the music you didn't like--is there any particular piece

you've written which stands as your favorite?

Circus:

How can you make money on a tour like you're now on, playing small halls

in relatively small cities?

Circus:

How can you make money on a tour like you're now on, playing small halls

in relatively small cities?

Circus:

When did you first start playing flute?

Circus:

When did you first start playing flute?

Circus:

Do you see music going in any direction?

Circus:

Do you see music going in any direction?