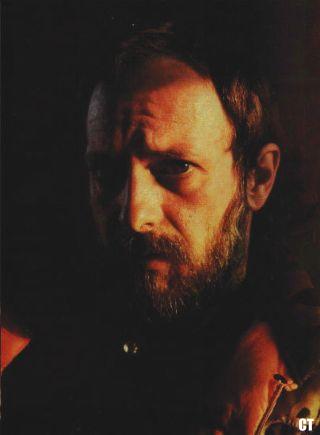

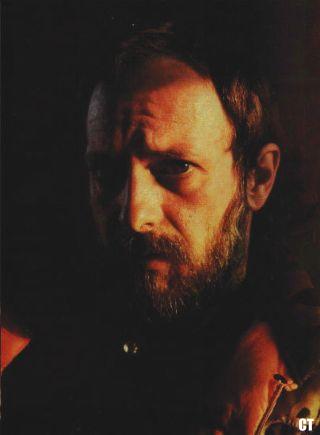

Jethro Tull

Kerrang [December, 1983]

"What a great view!" My eyes

ranged appreciatively over the wooded valley with its cottages nestling

near the village pub.

"Do you like it? It's

mine," said Ian Anderson, allowing himself a chuckle. The power behind

the throne of Jethro Tull has a kingdom most would envy. Some 600 acres

of rolling farm land are witness to the success and prestige of a band

whose career spans some 16 years. Anderson has towered above all versions

of this famous group exercising a quiet authority that commands respect.

It comes as no surprise

to learn that one of Ian's favorite pastimes is shooting and that he is

an expert on guns. He's not interested in the cowboy image of a trigger

happy lunatic, mind. For him the appeal lies in the cold hard discipline

of the marksman.

Along with Frank Zappa,

Paul McCartney and very few rockers, Ian Anderson has that quality of exuding

intelligence, while putting people at ease. He's funny, just a trifle tetchy,

takes a delight in gossip, and has an active mind that wants to probe and

rapidly share with others his interests and discoveries. Within minutes

of arriving at Ian's secret studio, a hop and a skip away from his rambling,

red brick country house, he was blinding me with the science of rock's

new technology. Linn drum machines were explained, mixing desks revealed

and new recording ideas unveiled.

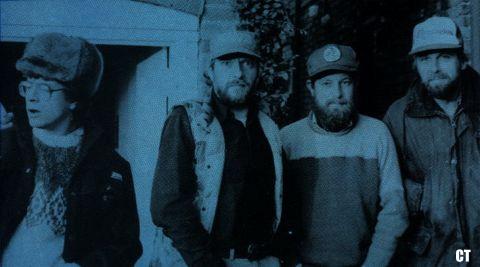

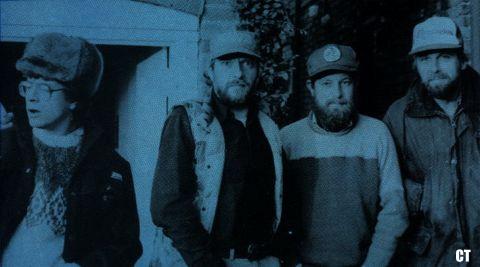

Down on the farm with

Ian were component parts of the latter day Jethro Tull. Peter-John Vettese,

a wild young Scot with a penchant for driving backwards and dancing in

fountains, who helped Ian make his first solo LP 'Walk Into Light' and

is now a fully fledged Tull man, as well as the stalwarts Martin Barre

on guitar and Dave Pegg on bass. All they need now is a drummer. Say Dave

and Pete. "He must have vast amounts of technique, be very loud, good looking

and have own transport."

It would seem an easy

enough job for Tull to call up the finest drummers in rock. Just get on

the blower to Simon Phillips and all problems are solved. But Tull's music

is a special case. They have a history of music going back to the days

of 'Aqualung' and 'Thick As A Brick'. And there are the milestones of the

last ten years, like 'Songs From The Wood', 'Heavy Horses', and 'StormWatch'.

Now Ian is interested in bringing the band's sound into the Eighties. On

his solo LP the emphasis is on keyboards rather than guitars and flutes,

so any new drummer brought into the Tull ranks must be both up to date

and sympathetic to past achievements.

Now Ian is interested in bringing the band's sound into the Eighties. On

his solo LP the emphasis is on keyboards rather than guitars and flutes,

so any new drummer brought into the Tull ranks must be both up to date

and sympathetic to past achievements.

For Ian it's no problem,

however. Ever since he started the band way back in 1968, he has been busy

exploring, expanding and changing. The wildly eccentric vision of the Pied

Piper of Hamelin, hopping around on one leg while blowing his flute, is

one of rock's most famous images. But it has always concealed a complex,

intense man. The crazed character who lurches around the stage, twirling

his flute with a dexterity on a par with that displayed by Roger Daltrey

in his microphone spinning feats, comes into existence only seconds after

Ian Anderson hits the stage. From then on he throws himself into the part

- a manic, medieval character...

He's had a motley crew

of musicians with him over the years, from Mick Abrahams, the guitarist

who quit to form Blodwyn Pig, to the most recent superstar to grace the

band's ranks, keyboard and violin man Eddie Jobson. But Ian is the figure

the public recognize as the personification of Jethro Tull, a man who can

still pack 'em in.

As we sat in the pub

he mused over a range of Tull Topics including the fact the band had wanted

to play in the Falkland Islands, not long after the war. They had been

asked to visit Argentina just after their American tour.

"We were on a sort

of unofficial peace mission But it meant staying for five days in a hotel

in Buenos Aires. So I sent a rider saying we wanted an armed guard and

I wanted a permit to carry a sub-machine gun. I didn't want to rely on

those guys to look after me.

"But with all the conditions

laid on by us, they decided it wasn't such a good idea, so we didn't go.

There was a lot of bad feeling towards the British, though probably not

from the young kids who would have come to the show. We were more worried

about the reaction of the police. I also wanted to play a gig in the village

hall in Port Stanley for the troops. If we had played both places it would

have been seen to be nonpolitical. But there was no way we could do it."

The last time I saw

Tull was at Wembley last year. Ian thought it had been: "A terribly hard

hall to play. I went to see David Bowie at Wembley and was dismayed at

the sound. I've never heard such a bad sound in my life. Every night there

was a post mortem on the Bowie tour, though I imagine we sounded pretty

awful as well. I'm sure people who like us don't want to see us at Wembley.

We only did it because we couldn't get the Odeon."

But surely Ian had

touring off to a fine art by now?

"Reasonably so, yes. We do it as cheaply as we can. We still make money

on the road and there aren't many bands who ever did. Certainly, there

can't be many now. Dave Bowie made an awful lot of money on the road, but

that's an event. We just make modest profits, regularly."

"Reasonably so, yes. We do it as cheaply as we can. We still make money

on the road and there aren't many bands who ever did. Certainly, there

can't be many now. Dave Bowie made an awful lot of money on the road, but

that's an event. We just make modest profits, regularly."

Most of next year will

be taken up with a world tour which sees the band coming to Europe in the

Autumn - to promote a new album. Although there is an enormous amount of

Tull activity, when you mention their name to people they often gasp: "Are

they still going?" Despite this, however, they have a vast, planet wide

following, something that makes the need to get a new drummer all the more

urgent. Said Ian:

"If anybody has any

bright ideas, do write to Chris Welch at Kerrang.', sending him your tape

and he will judge your competence and credentials, passing on to us the

best of the bunch. We worked with a good drummer last year, Paul Burgess,

and he was very solid and steady. What we are looking for is somebody a

bit more aggressive and fiery, and with a creative input. We want to avoid

the type who's able to throw it around but can't count as far as four.

There is one drummer in the world called Terry Bozzio who is just terrific

but, unfortunately for us, he is doing very well with his band Missing

Persons, and is not available for hire. He's the kind of guy we need."

Ian divides his time between

music and the businesses he wisely invested in during the boom years of

rock. Unlike so many of his contemporaries who drank away their inheritance,

Anderson put his money into schemes such as the salmon farm in Inverness,

opened by Quo fan Prince Charles. One of his ambitions is to build an underground

futuristic house, or else live in a 13th century Scottish castle.

"Farming is part of

my livelihood these days, and my wife Shona runs that side of things. Sometimes

life gets schizophrenic when I'm torn between different worlds, but it's

therapeutic not to get caught up in one kind of world. No way would I like

to spend my days sitting on a tractor, but then I would not like, at this

point in my life, to be a musician and nothing else. I like music to be

something that is fun. I don't want to feel I need music to make a living.

Hence the farms have got to be profitable and self supporting. I won't

be doing music forever - just nearly forever!"

Has Jethro Tull lasted

longer than he thought it would?

"Oh yeah. I remember

in 1970 coming back from an American tour and saying: 'That's it, I'm definitely

giving up. I'm now going to be something else. A record producer or something.

I enjoy playing concerts but I don't enjoy the pressures of touring, the

traveling and the hotels'. I'm adjusted to hotels now, though, and enjoy

the drinks, the bar and all that. But traveling, unfortunately, has got

a lot worse. I'm a very bad flier now, I didn't used to mind but, with

the passing of the years, and with a few engines dropping off, you feel

you've used up your nine lives."

How did Ian look back

over the history of Tull. Did he think much about the early days of 'Stand

Up' and the hit singles, 'Living In The Past' and 'Witches Promise'?

"I don't keep any memorabilia

at all. I have nothing from those days. I have never kept any of the records

or photos. That is my entire record collection right there (he pointed

to a tiny row of LPs dwarfed by vast masses of books on guns and country

life). I don't buy records and I don't have any Jethro Tull albums, except

a lot of test pressings.

So he felt no nostalgia

for the past?

"I'm afraid not, no.

Nostalgia is absolutely limited to stories told in bars in darkest Dusseldorf.

Martin has been with us longest, so he probably has a few 'Do you remember

when?' stories, although Dave Pegg has been with us since 1978. It's six

years which I think of as quite short, though for the average band it's

about two life cycles."

So what lures Ian back

to the rock business, year after year?

"It's the old thing

of walking out on a stage and seeing an audience who've turned out to come

to the show. It means a lot to them and you owe them a lot, too.

"For ten years we haven't

had a manager so we've had to do things ourselves. Jethro Tull is the archetypal

underground group we've been underground really since 1972. In Britain,

we had one Number One album in 1969 and after that we were considered old

hat. 'Aqualung' sold five million worldwide but only scraped into the Top

Twenty. All of our albums since have scraped into the charts, but that's

about it."

Tull enjoyed early

success In Britain but from then on seemed to be always in the shadows,

without much publicity or promotion.

"It's partly out of

choice, I suppose," says Ian. "It was nice to have an audience without

constantly promoting yourself in an obvious manner. It's hard to go into

the local supermarket shopping when you're a star. It's nice to be known...

but not TOO well known!

"It's moving for us

when we play and sell out a concert without any publicity, though. Particularly,

when we know that a lot of current Top Twenty jobs would have a hard job

selling out the same venue. We can do it without advertising, very quickly.

We have that hard core following of fans. We can do one show at the NEC

in Birmingham while Genesis can do five. Poor old Tull can only manage

one show at the NEC, but 8000 people in Birmingham on a wet night isn't

bad.

"Everybody gets their shot

at fame and greatness, but to maintain it on a regular basis is the province

of only a select few. I don't have any favorite Tull albums - only songs."

How did Ian feel about

the early birth pangs of the group when it used to undergo regular changes

in personnel?

"Well, it was never

that HAPPY a band in the early days because, as we gained success here

and then in America, we were subjected to a lot of pressure. We had to

learn to cope with success and being sought after by the press. Obviously,

some people can't cope with it all and go completely crazy. I don't look

on it as being a very enjoyable time. Certain gigs were fun to remember

but, overall, I wouldn't say I enjoyed much about our early years because

of the constant work and never having any holidays.

"I was homeless until

1975. I just lived in hotels. By then I was 30 and at that age most people

have got a couple of kids, a mortgage on a house and a car. I hadn't even

been skiing there were just loads of things I hadn't done which others

take for granted.

"I'm not a workaholic,

but I've tended to put money into tangible things. Basically, I like to

think I've given people jobs."

There have never been

Tull reunions. Was this something that appealed to him?

"Not in an organized sense

no. But we bump into people occasionally. John Evans (keyboard player between

1971-79) surfaces from time to time, and so does Eddie Jobson. We do actually

communicate even if past incarnations of the band didn't lead to lasting

personal friendships . Any animosity that might have existed in the past,

I don't think exists now."

Ian met Jack Bruce

recently and asked him if Cream was going to reform.

"His answer was the

same mine would be about getting together with ex-members of Jethro Tull

-- it's water under the bridge Whatever problems there were in the past

with personal relationships could be pushed aside but, after a couple of

months on the road, the same old thing would start to happen again. So

I don't think it's a good idea to go back.

"It's interesting to

see Yes have reformed and The Animals too, although that was anything but

happy! Alan Price and Eric Burden having set-tos in the dressing room...

They had a big fight at the Albert Hall apparently and Eric Burden went

missing just before their American tour. . ." Ian shook his head in amusement.

Ian made his solo album

last September before starting work with the band on the new Tull LP.

"I haven't played my

solo album since we made it. I've sort of forgotten it. I can't really

remember what it's about."

I reminded Ian that

the lyrics were straightforward and not fanciful, and that it represented

a move into the world of microchip powered keyboards.

"The whole point of the solo

album was to do new things I hadn't done before. Particularly, I wanted

to learn about recording again. I'd not been keeping abreast of what's

going on. These days a high standard is expected and delivered. So I sold

my studios, Maison Rouge in London, and set up at home. I've got all my

gear here. I wanted to do an album that wasn't all electric guitars and

flutes, and different from what people expect me to do. So it's based on

keyboard technology with Peter playing most of the keyboards. Peter came

into Tull through an ad in a trade paper. He joined in late 1981."

The new Tull LP will

be released next April and the band also hope to do a charity show for

the World Wildlife Fund to raise money for them to buy a mainframe computer.

Ian's special interest is 'acid rain' which the Fund are researching, and

the facts will be stored on the computer. Was he looking forward to performing

live again?

"Yeah, until I did

a live TV spot recently I hadn't been out in front of an audience for a

year. It's funny, I remember when I first started playing music my father

said if I cut my hair he'd buy me a wig I could wear on stage, as It was

obligatory to have long hair at the time. I have my hair short now, except

in the front where it won't grow anymore! I'm joining the ranks of Phil

Collins and Gary Numan."

Written by: Chris Welch

Now Ian is interested in bringing the band's sound into the Eighties. On

his solo LP the emphasis is on keyboards rather than guitars and flutes,

so any new drummer brought into the Tull ranks must be both up to date

and sympathetic to past achievements.

Now Ian is interested in bringing the band's sound into the Eighties. On

his solo LP the emphasis is on keyboards rather than guitars and flutes,

so any new drummer brought into the Tull ranks must be both up to date

and sympathetic to past achievements.

"Reasonably so, yes. We do it as cheaply as we can. We still make money

on the road and there aren't many bands who ever did. Certainly, there

can't be many now. Dave Bowie made an awful lot of money on the road, but

that's an event. We just make modest profits, regularly."

"Reasonably so, yes. We do it as cheaply as we can. We still make money

on the road and there aren't many bands who ever did. Certainly, there

can't be many now. Dave Bowie made an awful lot of money on the road, but

that's an event. We just make modest profits, regularly."