Jethro Tull

Circus Magazine [November, 1974]

As Ian Anderson mused on the "retirement" ruse, he was temporarily ensconced

in a windowed cage, one of the chic new luxury apartment buildings that

are beginning to line Sunset Boulevard just above the strip like plastic

warts on a road map. The reclusive, usually unwilling candidate for an

interview was granting Circus Raves the special privilege of his conversation

in honor of his newest presentation, War Child (on Chrysalis Records),

a production that Ian intends to enjoy despite whatever criticism or audience

reaction it may bring. War Child, as the title implies, is actually a hostile

response to last year's debacle with Passion Play, an aggressive position

being taken by a musician who last year was willing to pull up his stakes

and run.

As Ian Anderson mused on the "retirement" ruse, he was temporarily ensconced

in a windowed cage, one of the chic new luxury apartment buildings that

are beginning to line Sunset Boulevard just above the strip like plastic

warts on a road map. The reclusive, usually unwilling candidate for an

interview was granting Circus Raves the special privilege of his conversation

in honor of his newest presentation, War Child (on Chrysalis Records),

a production that Ian intends to enjoy despite whatever criticism or audience

reaction it may bring. War Child, as the title implies, is actually a hostile

response to last year's debacle with Passion Play, an aggressive position

being taken by a musician who last year was willing to pull up his stakes

and run.

"You know, I only wrote

two songs anyway," Ian said, sweeping his hand across the room as if the

songs were lined up in a display case in front of him. "I'm always writing

the same two songs and I always will, because I'm concerned with two sorts

of ideas. To get to the bottom of those two ideas in terms of pop music."

Passion Play, as Ian explained,

represented one of those ideas, that of good and evil "as two kinds of

polarity that exist. The other idea, of loving and hating, is what War

Child is about, and it probably represents most of the notions of criticism

and acclaim Anderson has been harboring for years. "If I reduce things

to those standards it makes it easier for me, as well as making it easier

for the pope, the archbishop and Billy Graham among others.

"We all tend to reduce

things to absolute standards and, as well as we can, conduct our lives

in a suitably acquiescent manner. It's a fault of human kind to do that,

and me too. But I expect that it's the easy way of going about it. So I

do it as well."

War Child, then, another

LP of epic proportions and heartfelt sentiment, has become Ian's answer,

his philosophy, to the dog-eat-dog world he suddenly realized he was caught

in when the critics demolished Passion Play. "We're all animals, competing-aggressive,

out to win at the expense of others. And we have our codes, our rules and

laws that we've invented which are convenient within the context that we

operate. At this point in history the rules are one way. They change throughout

the ages. But if aggression and competition is what everybody wants to

do then I'll go along with it."

Quest for best world:

Ian's quest for better living began in Blackpool, England, a gaudy and

cheap resort to the southeast of London. Arriving in London in 1967, he

formed the group Jethro Tull, and later released his first LP, This Was,

in January of 1969. His next, Stand Up, a few months later, was shortly

followed by Benefit, released in April of 1970. Each album progressively

became more popular with audiences, until finally Benefit turned gold,

dragging Stand Up along with it. Ian still had a way to go to achieve superstardom.

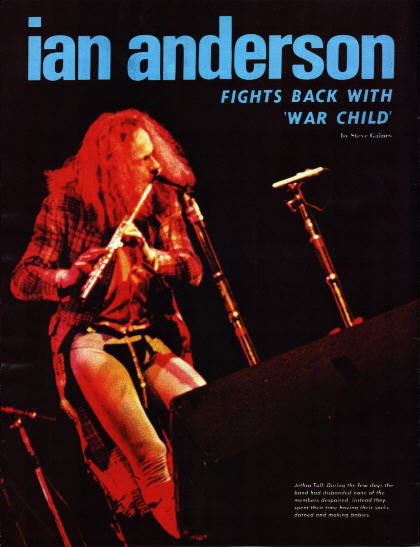

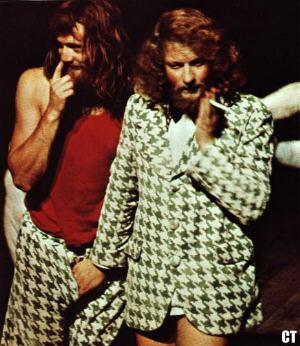

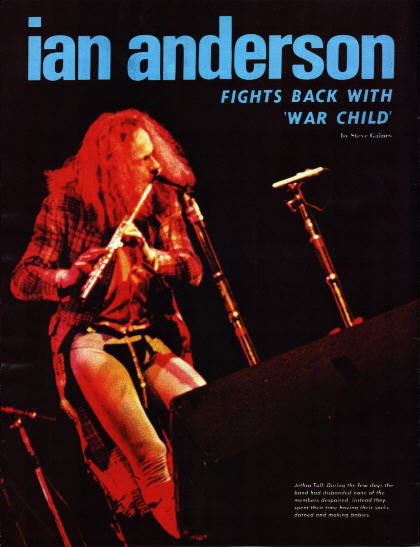

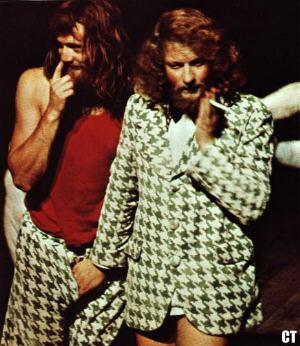

Touring followed, and still more tours. When the public got the opportunity

to see Ian, a bulging eyed, codpieced, hopping maniac, Ian's popularity

grew with each ballet leap across sold-out concert halls. Then Aqualung

happened.

Touring followed, and still more tours. When the public got the opportunity

to see Ian, a bulging eyed, codpieced, hopping maniac, Ian's popularity

grew with each ballet leap across sold-out concert halls. Then Aqualung

happened.

Described as a pro-God

statement concerning the church, it was the first of Ian's message albums.

The problem was. nobody wanted Ian's message. Stranger still, the message

didn't matter; if his audience didn't understand what he was trying to

say, they liked the sound of the words nevertheless. The grave moral commandments

were as thick as a brick.

Not coincidentally,

Thick As A Brick was the album that quickly put Ian into superstar category,

and the following LP, Passion Play, quickly took him out of the same league.

Fans could forgive Ian for not liking one of his albums (although it sold

remarkably well and was not unsuccessful financially by any means) Ian

could not forgive his fans.

After Passion Play,

and Ian's press blackout in English speaking countries, there followed

an eight month silence during which Jan rearranged his thoughts and decided

on a new tack for his music. Since he couldn't always satisfy the critics,

he decided to satisfy himself instead.

"Writing is a convenient

way of shaving," Ian said mysteriously, shouting his words as he loped

into the kitchen to put up a pot of his favorite drink--coffee. "I have

a shaving mirror in the form of a lot of lyrics and a lot of songs which

I sit and think about sometimes, and sometimes I wish I hadn't written

them. I'm not as concerned with saying things for other people as I am

with saying things for myself. I'm not just fooling around. I'm aware that

other people are occasionally moved by what I write.

"Put when critics give

a lukewarm reception to Yes and Emerson, Lake and Palmer, one detects that

it's not the fault of the music but the fault in the taste of a man whose

job is made easy by listening to shorter pieces. Critics shouldn't make

the people think they're the final judge of what is good and what's bad.

A punch in the nose is the only answer I have to derogatory comments."

Revolving door: But

instead of a punch, Ian crawled into a little ball and quit - at least

for a short time. Even if Ian had never decided to go back to work again

he would never be in need of money. Although rock stars like Elton John

and groups like Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin seem to be rolling in money

(and they are), Ian Anderson is among the richest rock performers in the

world. First of all, he has a strong reputation for being frugal. Secondly,

the Jethro Tull band are not partners in Ian's music. They are salaried

performers, a group of musicians who were so disenchanted with their small

wages that, for a time, the Jethro Tull group appeared to have a revolving

door through which members both left and entered the group. Almost all

the riches of Jethro Tull are shared by Ian and his manager, Terry Ellis.

Due to increased salaries in the band, though, the membership has remained

stable for almost three years now.

The creative process

of Ian Anderson is at once as mysterious and fascinating as Ian himself.

He calls the process "musical doodles," and as he explains it, his songwriting

takes on a mysterious, seance-like aura. Most musical ideas, he says, begin

in hotel rooms, or his own house where he plays and works ideas out. "The

things that appeared the most calculated on my albums were figured out

on the spot," the bearded, hazel-eyed musician explained earnestly. "For

example, the 'Story of the Hare' and the two pieces that surround it on

the Passion Play were not carefully arranged and figured out. If you know

music you'll realize that there are time sequences that cross themselves.

It's appealing and interesting, but I could never have done it twice. I

can never even remember lyrics to songs until I get onstage, and thank

God I can remember them then."

Time

warp: The music that is carefully planned is shrouded in a spiritual creative

process, almost like a trance. "I sit down in the middle of the night,"

Ian said, pausing for a sip of black coffee, "and I have a song in my head

and I have inevitable words for that song. Maybe it's only one line or

three words or two words--that belong there. It just comes out--it's in

my head, and everything then follows on from there. I'll write that word

on a piece of paper and I sit there and stare at it and other words start

to appear on the paper. At the end of half an hour I might have four or

five lines. But," Ian exclaimed, raising his eyebrows, "I haven't written

those lines in the sense that I've been trying to make words rhyme. Time

has no meaning for the 20 minutes or half hour that I'm writing. Suddenly

the words are there. I go and make a cup of coffee and go upstairs and

look at them and say, 'Oh, fancy I did that in the last half hour'."

Time

warp: The music that is carefully planned is shrouded in a spiritual creative

process, almost like a trance. "I sit down in the middle of the night,"

Ian said, pausing for a sip of black coffee, "and I have a song in my head

and I have inevitable words for that song. Maybe it's only one line or

three words or two words--that belong there. It just comes out--it's in

my head, and everything then follows on from there. I'll write that word

on a piece of paper and I sit there and stare at it and other words start

to appear on the paper. At the end of half an hour I might have four or

five lines. But," Ian exclaimed, raising his eyebrows, "I haven't written

those lines in the sense that I've been trying to make words rhyme. Time

has no meaning for the 20 minutes or half hour that I'm writing. Suddenly

the words are there. I go and make a cup of coffee and go upstairs and

look at them and say, 'Oh, fancy I did that in the last half hour'."

After the words "appear"

on paper Ian goes back to them and makes alterations and strengthens the

beginning of thoughts. "It's very automatic. I'm dealing with images all

the time and everything I write operates on at least two levels."

Happy aggression: This

was the manner in which War Child was written, and the results are another

staggering, brilliantly blended potpourri of the kind that made Ian famous

to begin with. "The overall theme of War Child is that all of us have a

very aggressive instinct which is something we're occasionally able to

use for the betterment of ourselves. At other times, aggression at its

worst is used as a very destructive element. When it's not at its worst

it remains merely comical. I don't think that aggression is such an evil

thing."

Still gunshy of the

press, Ian would rather let the War Child album speak for itself; but he

did mention some fascinating aspects of some of the cuts. The main theme

is ensconced in a song entitled "Bungle in the Jungle," a song that states

that if aggression is the way of life, it's fine with Ian, as long as we're

aggressive with a smile.

Lets bungle in the

jungle

That's all right by me...

As the hail of criticism

fell on the unprotected ego of rock's most sensitive musician, the leader

threw up his hands and quit. But two days later he was back composing,

and now only eight months later he's popped up with a staggering LP that

proves Jethro Tull is still tops.

There are hours of

recorded music that never even made it onto acetate. "We recorded enough

material for two albums. We drifted off into a 50 piece orchestra and I

have 20 minutes worth that no one will probably ever hear."

One of the cuts that

will appear on War Child happened in the most casual way. "I was coming

out of my office one day and saw this youngish person outside of Selfridge's

(a London department store), which is very close to the Chrysalis office

in London. There was this bagpipe music being played. I, as a Scotsman,

was immediately enticed to riot. Having found the source of the dreadful

noise, I enjoined the young gentleman responsible to procure another two

players and come to rehearsal." Subsequently the bagpipe players appear

on a cut entitled "The Third Hurrah."

"I had in mind to put

pipes on all along, without any thought as to where I would pet them."

War

Child is more than the next step in a progression of albums, from this

brilliant, sensitive and confusing artist; it's part of the continuing

work of the best avant-gardist in the music business. For Ian, music doesn't

end with a piece of acetate that had his melodies and lyrics recorded on

it. Music is a very visual concept to Ian, and thus he made a film to go

along with Passion Play. Not only is War Child recorded in quadraphonic

sound--and Ian urges all music fans who can afford a quad unit to buy one--but

it's also going to be a full length motion picture that incorporates his

music. Yet that isn't futuristic enough to satisfy the incredible master

of Jethro Tull. Next is the building of a mobile recording studio, and

what Ian calls "Video Product."

War

Child is more than the next step in a progression of albums, from this

brilliant, sensitive and confusing artist; it's part of the continuing

work of the best avant-gardist in the music business. For Ian, music doesn't

end with a piece of acetate that had his melodies and lyrics recorded on

it. Music is a very visual concept to Ian, and thus he made a film to go

along with Passion Play. Not only is War Child recorded in quadraphonic

sound--and Ian urges all music fans who can afford a quad unit to buy one--but

it's also going to be a full length motion picture that incorporates his

music. Yet that isn't futuristic enough to satisfy the incredible master

of Jethro Tull. Next is the building of a mobile recording studio, and

what Ian calls "Video Product."

"Video Product" is

an idea that has been kicking around the media electronics back rooms for

a long time, and now that commercial machines are available to play a "video

disc," Ian promises his next album will be recorded in that way. "The system

should only cost $500.00. It will connect between an existing stereo and

a television set. When you play a record, the proper accompanying visuals

will appear on your TV screen."

Tull war path: Although

Ian's new found security in his "aggressive" attitude towards life seemingly

will protect him from the critics, if they again do not bless his baby,

War Child, only the massive tour planned for the next 18 months will tell

the true story. Beginning in the United States in late September, Ian's

new tour will consist of the best of Jethro Tull, from Thick as a Brick

and Aqualung right through Passion Play and War Child. But this time, if

nobody is turned on to Jethro Tull. Ian just doesn't care.

"I'm too honest to

say that I play for the audience every night. I don't. I go out and play

for me. But if I notice they happen to be enjoying it, I like that very

much.

"Everybody must be

impressed with what they're doing." Ian concluded. "Without a self-paid

compliment none of us have a lot to hope for. If you rely solely on other

people's compliments you get desperate because you have to seek that approval

from people all the time.

"It's only the inner

knowledge of success that pays off."

Maybe Ian has found

that inner knowledge. and will not despair any longer of criticism, whether

from the critics or the people that come to see his shows and buy his records.

After all, a rock star is a performer, but not a servant. And the release

of War Child seems to confirm that in the past year Ian has learned more

about himself than we have about his music.

Written by: Steve Gaines

As Ian Anderson mused on the "retirement" ruse, he was temporarily ensconced

in a windowed cage, one of the chic new luxury apartment buildings that

are beginning to line Sunset Boulevard just above the strip like plastic

warts on a road map. The reclusive, usually unwilling candidate for an

interview was granting Circus Raves the special privilege of his conversation

in honor of his newest presentation, War Child (on Chrysalis Records),

a production that Ian intends to enjoy despite whatever criticism or audience

reaction it may bring. War Child, as the title implies, is actually a hostile

response to last year's debacle with Passion Play, an aggressive position

being taken by a musician who last year was willing to pull up his stakes

and run.

As Ian Anderson mused on the "retirement" ruse, he was temporarily ensconced

in a windowed cage, one of the chic new luxury apartment buildings that

are beginning to line Sunset Boulevard just above the strip like plastic

warts on a road map. The reclusive, usually unwilling candidate for an

interview was granting Circus Raves the special privilege of his conversation

in honor of his newest presentation, War Child (on Chrysalis Records),

a production that Ian intends to enjoy despite whatever criticism or audience

reaction it may bring. War Child, as the title implies, is actually a hostile

response to last year's debacle with Passion Play, an aggressive position

being taken by a musician who last year was willing to pull up his stakes

and run.

Touring followed, and still more tours. When the public got the opportunity

to see Ian, a bulging eyed, codpieced, hopping maniac, Ian's popularity

grew with each ballet leap across sold-out concert halls. Then Aqualung

happened.

Touring followed, and still more tours. When the public got the opportunity

to see Ian, a bulging eyed, codpieced, hopping maniac, Ian's popularity

grew with each ballet leap across sold-out concert halls. Then Aqualung

happened.

Time

warp: The music that is carefully planned is shrouded in a spiritual creative

process, almost like a trance. "I sit down in the middle of the night,"

Ian said, pausing for a sip of black coffee, "and I have a song in my head

and I have inevitable words for that song. Maybe it's only one line or

three words or two words--that belong there. It just comes out--it's in

my head, and everything then follows on from there. I'll write that word

on a piece of paper and I sit there and stare at it and other words start

to appear on the paper. At the end of half an hour I might have four or

five lines. But," Ian exclaimed, raising his eyebrows, "I haven't written

those lines in the sense that I've been trying to make words rhyme. Time

has no meaning for the 20 minutes or half hour that I'm writing. Suddenly

the words are there. I go and make a cup of coffee and go upstairs and

look at them and say, 'Oh, fancy I did that in the last half hour'."

Time

warp: The music that is carefully planned is shrouded in a spiritual creative

process, almost like a trance. "I sit down in the middle of the night,"

Ian said, pausing for a sip of black coffee, "and I have a song in my head

and I have inevitable words for that song. Maybe it's only one line or

three words or two words--that belong there. It just comes out--it's in

my head, and everything then follows on from there. I'll write that word

on a piece of paper and I sit there and stare at it and other words start

to appear on the paper. At the end of half an hour I might have four or

five lines. But," Ian exclaimed, raising his eyebrows, "I haven't written

those lines in the sense that I've been trying to make words rhyme. Time

has no meaning for the 20 minutes or half hour that I'm writing. Suddenly

the words are there. I go and make a cup of coffee and go upstairs and

look at them and say, 'Oh, fancy I did that in the last half hour'."

War

Child is more than the next step in a progression of albums, from this

brilliant, sensitive and confusing artist; it's part of the continuing

work of the best avant-gardist in the music business. For Ian, music doesn't

end with a piece of acetate that had his melodies and lyrics recorded on

it. Music is a very visual concept to Ian, and thus he made a film to go

along with Passion Play. Not only is War Child recorded in quadraphonic

sound--and Ian urges all music fans who can afford a quad unit to buy one--but

it's also going to be a full length motion picture that incorporates his

music. Yet that isn't futuristic enough to satisfy the incredible master

of Jethro Tull. Next is the building of a mobile recording studio, and

what Ian calls "Video Product."

War

Child is more than the next step in a progression of albums, from this

brilliant, sensitive and confusing artist; it's part of the continuing

work of the best avant-gardist in the music business. For Ian, music doesn't

end with a piece of acetate that had his melodies and lyrics recorded on

it. Music is a very visual concept to Ian, and thus he made a film to go

along with Passion Play. Not only is War Child recorded in quadraphonic

sound--and Ian urges all music fans who can afford a quad unit to buy one--but

it's also going to be a full length motion picture that incorporates his

music. Yet that isn't futuristic enough to satisfy the incredible master

of Jethro Tull. Next is the building of a mobile recording studio, and

what Ian calls "Video Product."